Bloomberg: Mapping the Political Fallout of GOP Health-Care Cuts

The GOP’s cuts to federal health-care spending are likely to be a marquee issue in next year’s midterm elections. And this week, Senate Republicans are poised to significantly increase the number of states and House districts where Americans will feel the bite.

In a vote scheduled for Thursday, Senate Republicans are virtually certain to block the extension of the enhanced subsidies that former President Joe Biden and Congressional Democrats passed to lower the cost of purchasing private insurance through the Affordable Care Act.

With that, Republicans will complete a picture they started by passing the “One Big Beautiful Bill” last summer. That legislation imposed the largest reduction ever in Medicaid — more than $900 billion through 2034 — targeted predominantly at states that expanded eligibility for the program under the ACA to millions more low-income working adults. The Congressional Budget Office projects the Medicaid cuts will revoke health insurance from 10 million people. About four million more would lose coverage from ending the enhanced ACA subsidies, with about 20 million others facing higher premiums.

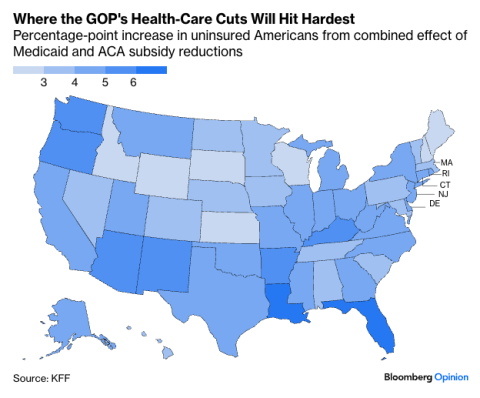

The ACA subsidies and the Medicaid expansion operate as a seesaw: in most of the 40 states that expanded Medicaid eligibility, relatively fewer people rely on the ACA subsidies, while in the ten (mostly Republican-controlled) states that refused to expand Medicaid, far more people rely on the subsidies. The cumulative effect of cutting both programs will be to greatly expand the blast radius of places facing direct fallout from the GOP’s health care decisions.

“It’s a combined punch,” said Larry Levitt, executive vice president for health policy at KFF, a non-partisan health care think tank. “The Medicaid cuts and expiration of the ACA premium tax credits are going to hit low-wage workers in all states.”

The interaction of the two programs explains their reinforcing effect. The ACA provided states with generous federal funding to expand Medicaid eligibility to adults earning up to $21,600 for an individual or $44,400 for a family of four. In the states that accepted that funding, only adults earning more than that can receive the ACA subsidies to buy private insurance. In the states that didn’t expand Medicaid, the subsidies are available to anyone with earnings above the poverty line; that means many low-income workers who would receive Medicaid if they lived in an expansion state instead rely on the subsidies. (In both the expansion and non-expansion states, the subsidies phase out for people earning more than four times the poverty level, around $63,000 for an individual.) Small business owners and employees, and adults near age 65 — a group that includes many retirees — are especially reliant on the ACA subsidies in both groups of states.

The reconciliation bill hammers the states that expanded Medicaid: KFF projects that over the next decade, the bill’s cuts will cause 1.3 million Medicaid recipients to lose their eligibility in California, 760,000 in New York, and 400,000 in Illinois. Conversely, KFF projects the expiration of the enhanced subsidies will swell the number of uninsured in states that didn’t expand Medicaid — including 1.5 million in Florida, 1.4 million in Texas, and 500,000 in Georgia.

A few states with big populations of low-wage workers fall into the dubious overlap of this Venn diagram and will face substantial coverage losses from the retrenchment of both the subsidies and Medicaid. These include states that will host marquee races next year for governor, senator, or both, such as Arizona, Michigan, Ohio and Pennsylvania.

The same pattern persists at the district level. KFF figures show that the Medicaid expansion covers large numbers of people in GOP districts that Democrats are hoping to flip in such expansion states as California, New York, and Virginia — as well as in Democratic seats Republicans hope to capture in New Mexico, Nevada and Maine.

The loss of the ACA subsidies, in turn, probably represents Democrats’ best chance to frustrate the effects of the unusual mid-decade redistricting Texas Republicans engineered under pressure from President Donald Trump. More than 100,000 people receive the enhanced ACA subsidies in three of the Democratic districts Republicans are targeting in heavily Latino South Texas, including the seat held by Representative Vicente Gonzalez.

Gonzalez told me the expiration of the subsidies will make insurance unaffordable for many more people in his district, which in turn will heighten the financial pressure on hospitals and doctors. “People are going to shutter their doors,” he said. “The Rio Grande Valley is already 1,000 physicians short. This will only create a more critical environment in the most uninsured region in the most uninsured state in the country.”

Over 150,000 people rely on the ACA subsidies in the South Texas seat that Representative Monica De La Cruz won in 2022, becoming the first Republican to do so in over a century. Bobby Pulido, the Tejano music star who is her likely Democratic opponent, told me the loss of the subsidies will “crush” the district and force more residents to seek care across the border in Mexico. “Being in this great country … we should be ashamed of ourselves that people are going to Mexico to get health care because it’s not affordable here,” said Pulido, who told me he is uninsured himself.

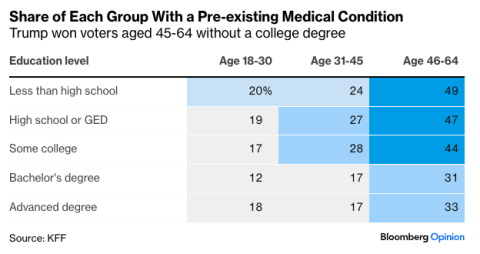

The cuts to both the ACA subsidies and to Medicaid will primarily affect low-income working people — the very voters Trump has wooed to the GOP electoral coalition. Moreover, far more House Republicans than Democrats, as I’ve written, represent districts with an above-average share of residents facing major health problems such as diabetes and cardiovascular issues. Older working-age adults without a college degree, long one of Trump’s best groups, are especially likely to confront chronic health problems: New calculations KFF provided to me show that nearly half of all non-college adults aged 45-64 suffer from a preexisting health condition, far more than people who are younger or have college degrees.

For decades, Republicans have bet they can win working-class voters with polarizing cultural issues, even if they pursue economic policies that damage their material interests. That wager has usually paid off, especially under Trump. But the GOP may be spinning the wheel one time too often with its two-front assault on access to health care.